TOUR DETAILS: Saturday July 10, 2021

WHERE: Bonaventure Cemetery & Erica Davis Lowcountry

TIME: Tour 9AM to 11:30 RECEPTION: 11:45 to 1PM

COST: $30 (30 Tickets Only!) LUNCH OPTIONAL

RESERVATIONS: Click BOOK NOW any page or call 912-319-5600

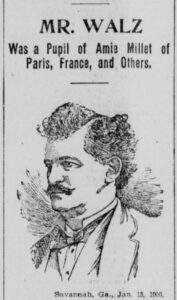

Shannon Scott will conduct a special FIRST ANNUAL tour dedicated to a portion of the 200 works of sculptor John Walz found in Bonaventure Cemetery with Little Gracie’s plot being the highlight. Shannon will present a never-before-seen artifact pertaining to Gracie’s life during tour. Cake Artist Extraordinaire Tina Arnsdorff Tina Bakes On Instagram will present the amazing Little Gracie inspired cake at Erica Davis Lowcountry Restaurant near Bonaventure and is not-to-be-missed!

“She adopts every passerby, every passerby adopts her….”

This has become a cultural credo for Savannah of sorts. My guests hear it every day as I tell them, “you cannot say that you’ve been to the Savannah village, you’ve not joined the spiritual ranks until you’ve gone to Bonaventure for the adoption moment with Little Gracie.”

Its hard to believe that a girl who died just a few months shy of her 7th birthday in 1889, is at least, in spirit, turning 139 on July 10th, 2021. The statue unveiled in 1891 so technically a tad younger but not by much. And 137 years later, this statue has become the most important locally made piece of portrait art that Savannah will ever know. She is literally irreplaceable.

The Tender Face of Gracie

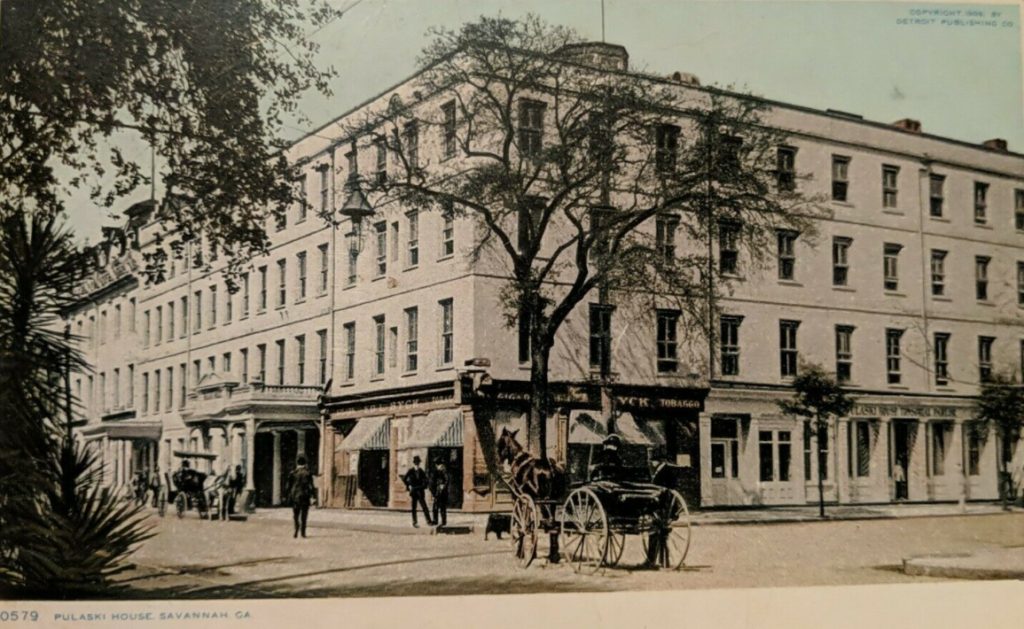

In 1889, newly famed and recently arrived Philadelphia sculptor, John Walz, had only been in town for a few days when in walks an early customer, hotel proprietor, Wales Watson. A man so bereft by the loss of he and wife Frances’ only child, Walz claimed they didn’t even speak. The father, who at first was unknown by name to Walz, simply handed him a photo of Gracie and turned around and left the studio. A powerful moment and an exchange perhaps not uncommon in such studios Pre-Pencillin 1928 when memorials to children paid every sculptor and stone cutter’s overhead in America and every parent the week a child was born, went to a bank and opened a Funeral Fund Saving’s Account.

In 1889, newly famed and recently arrived Philadelphia sculptor, John Walz, had only been in town for a few days when in walks an early customer, hotel proprietor, Wales Watson. A man so bereft by the loss of he and wife Frances’ only child, Walz claimed they didn’t even speak. The father, who at first was unknown by name to Walz, simply handed him a photo of Gracie and turned around and left the studio. A powerful moment and an exchange perhaps not uncommon in such studios Pre-Pencillin 1928 when memorials to children paid every sculptor and stone cutter’s overhead in America and every parent the week a child was born, went to a bank and opened a Funeral Fund Saving’s Account.

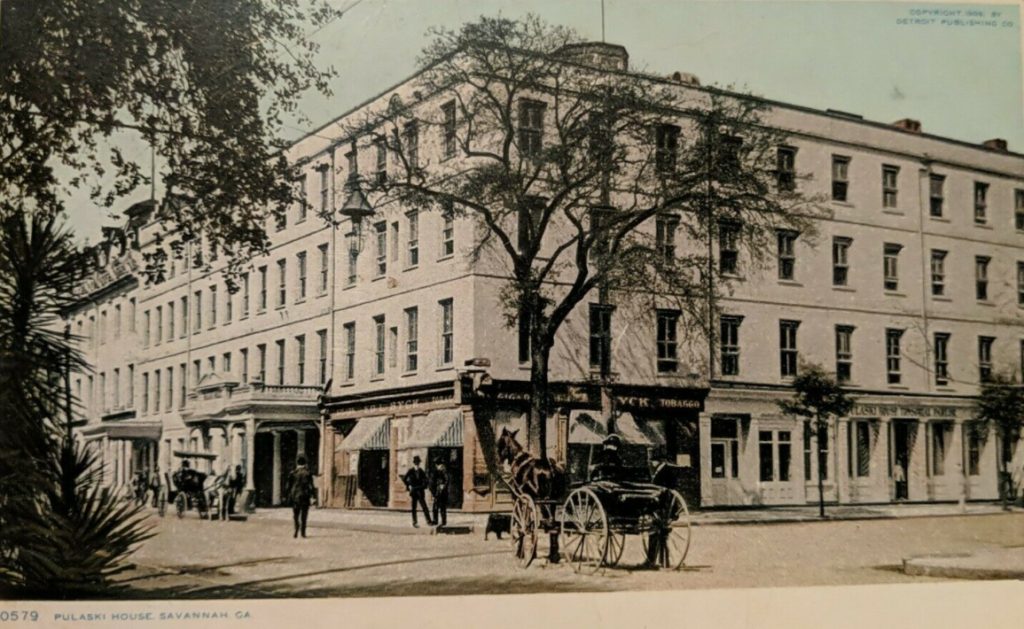

Gracie’s Childhood Home

Later in life, Walz, a man who’s crew had worked on Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain Georgia and he himself adding to The Gettysburg Battlefield, called his Little Gracie statue, “my life’s finest work.” As a father himself, how could she not be?

Eventually Little Gracie was left alone to fend for herself and both nature and some persons were not kind. In 1909 a local newsman called her plot “unrecognizeable.” It was that year, some of Gracie’s friends who outlived her, stood her statue upright, cut out the jungle that had consumed her plot and a grand tradition of traditions came to life wtih community caretaking. When you came out to Bonaventure, you always stopped by to check in on your other relative, Little Gracie. And just like they do now, children 100 years ago would fawn and leave toys while parents would leave money to aid in her protection and all very alms like. As I say to guests, “if there were a mountaintop in Savannah and a shrine near the peak, this is that shrine.” She is the people’s icon of thing’s eternal in The Church of Savannah, a non-denominational place. She is the eternal child spirit in everyone and the innocence we must always maintain some of and never forget or abandon. For if we do all of life and us in it becomes lost. Visiting Little Gracie is like personal life maintenance.

Gracie & The Hawk