“We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately”

— Ben Franklin

I’ve just returned from a rather cold 5-mile walk in the cemetery under a powerful full moon, or what’s leftover from last evening’s Super Blood Wolf Moon. My soundtrack? Dr. Martin Luther King’s historic speeches here on the nation’s annual holiday just several days after King’s birthday. There was something about the combination of the moonlight illuminating so brightly that objects became stark black and white, King’s God-like voice echoing off of granite and marble headstones like they were his gathered, listening flock. Sadly, King, now more among them, even if the legacy of his words and hypnotic voice live on forever and resonate as vibrantly if not more so.

It has become almost a ritual for me now that I give myself a Dr. King Day every January 20. Generally, I will turn on Savannah State University’s 90.3FM and listen to his speeches and the various interviews and commentaries they play. For an entire day, his voice fills both the foreground and the background of my household. It’s generally a day where I don’t leave the house much, I become that immersive in the spirit of his memory and the meaning of his life. I’ve found its usually a sunny, but colder day in Savannah on King’s Remembrance Day and am embarrassed to admit that I usually skip the morning parade. It’s just that the day wants me to be more meditative and singular, surrounded by my animals and books and the smell of coffee. More Thoreau-in-the-woods kind of experience. Martin would approve but would probably tell me to add a carton of Kent cigarettes. After all he was an intellectual before Minister.

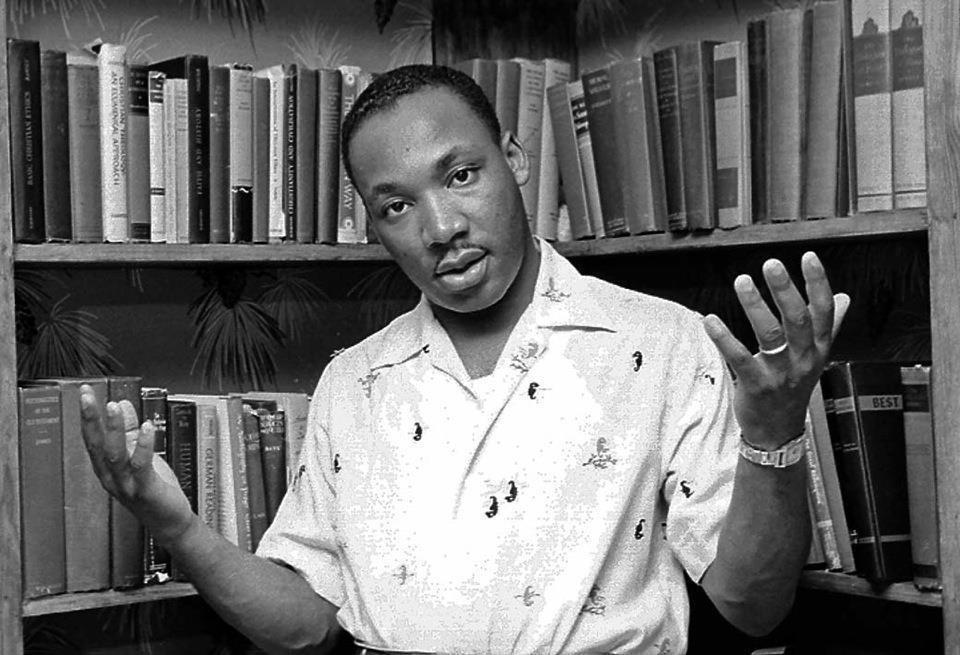

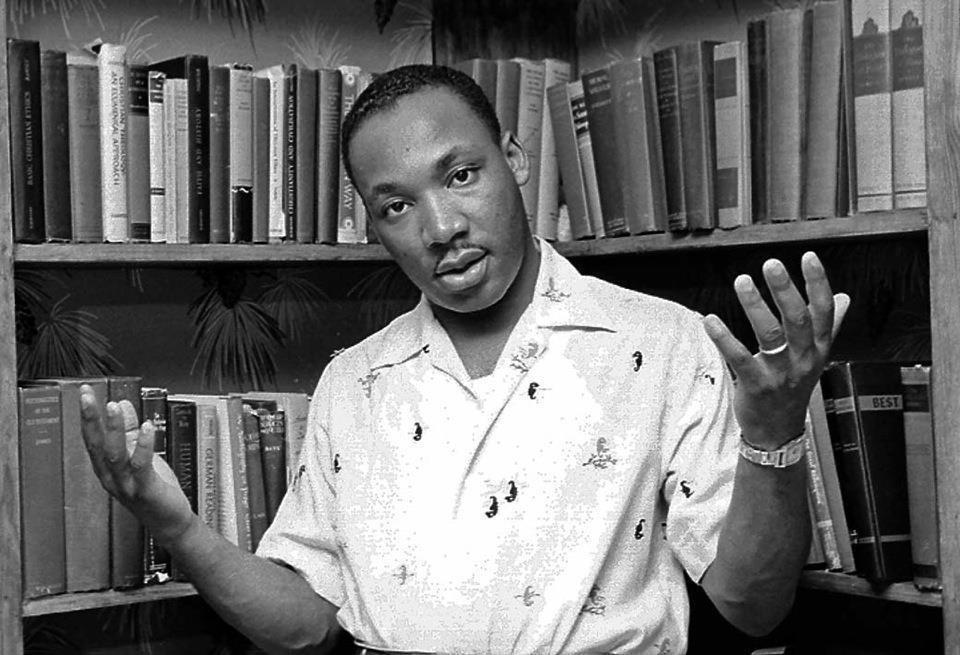

Young Martin Luther King, Jr, arms open in the way a book is like a friend. After so much reading, Martin was ready to be read like one and he spoke volumes.

Tonight I’m moved to write about Dr. King and The 6 Degrees of Civil Rights’ Separation in my own life. No, I was not there but I moved to a town that was center stage and have, met and in some cases befriended key players who knew other majors. I never got to meet my hero Dr. King, who, at a very young age, became part of my spirit and voice as communicator and orator and storyteller. So to meet people who did, to make studies of their faces and words as they’ve related this story or that one? And to now call these people “my new heroes,” or to have made the friendship of some? Well, I cannot begin to express how deeply its touched my life and that these memories I will carry with me until the end of my own days. I am gobsmacked when I think about it actually.

This will be a long night for me. But I’m channeling The King Energy so have to honor the muse and of course, you, my reader. There will be a Part Two & Three and will be worth holding out for so stay with me in this path. It will lead somewhere interesting and unexpected.

I’ve stood next to and touched a real live lynching tree. Like a real one. Not the ones they talk about on cheesy ghost tours, but a true-to-life, hanging tree. I used to sit on the bench beneath its massive branches late at night taking breaks from art projects, or in the afternoons when I watched my dog Mina play nearby. I loved its large presence and the way it stood behind me. It kept me company. I used to watch the sun go down behind it each night from my 5th Floor apartment 2 blocks away. All Live oaks seem to hold secrets but for a number of years, I had no idea that this one had such a dark past. A rather morbid irony was that it reposed smack dab in the middle of Colonial Park Cemetery. Like some great watchtower, it was the tallest Live oak in downtown Savannah and by some estimates around 120 ft in height. It was often compared to the height of the steeple of The Independent Presbyterian Church as it was visible from pretty much anywhere in the historic district. You can actually glimpse it in my documentary film, “America’s Most Haunted City” or peek it on YouTube in a CMT TV short I did with Coast To Coast Radio’s George Noory. The cemetery had been used for hangings during colonial times and the last mob-style lynching was in 1911. A black man falsely accused of raping a white woman was dragged from the neighboring Old City Jail, then hung from the mighty oak and his body was torched on the tree. The original photo, which had never been previously exhibited or publicly seen, was owned by a mentor who loaned it to the controversial exhibit “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” in 2002 at The King Center. My friend had spoken of it many times, so it was finally something to see it first hand. The image of the charred body forever burned in my mind. Like it was never a man from the start. I never blamed the tree obviously, but when the city cut the perfectly healthy tree down over a decade ago? I felt certain someone either still held a grudge or felt they were putting the tree out of its own historical misery. I wept over that one.

On a “lighter note,” there’s a neighbor who I’ve long respected, the family much admired, he owns a set of swivel stools from a drugstore counter where protestors sat in Savannah during a sit-in during the turbulent ’60s. They repose discreetly and unmarked in his storefront window. When I first asked him why they were there, this rather humble man and not famous for smiling, almost beamed back one when he exclaimed, “Dr. King sat in them and when they closed the department store, I told the man, “Save those chairs for me!” You could tell they’ve been a proud possession ever since.

On a “lighter note,” there’s a neighbor who I’ve long respected, the family much admired, he owns a set of swivel stools from a drugstore counter where protestors sat in Savannah during a sit-in during the turbulent ’60s. They repose discreetly and unmarked in his storefront window. When I first asked him why they were there, this rather humble man and not famous for smiling, almost beamed back one when he exclaimed, “Dr. King sat in them and when they closed the department store, I told the man, “Save those chairs for me!” You could tell they’ve been a proud possession ever since.

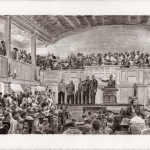

Although I once lived closer, I’m still just mere blocks from The 2nd African Baptist Church where Dr. King flirted with an early rendition of his famous, I Have A Dream speech. Arguably the greatest speech given in the 20th century and in my opinion is the only rival to “The Gettysburg Address.” Every goose bump from here to eternity now has a built-in reaction, programmed by King’s magnificent oration. Can you imagine having been part of the test audience on that one? And in the same spot, where many years prior, General Sherman had presented his 40 Acres & A Mule edict? Talk about nation changing speeches and what a follow-up for the young Rev King!

-

-

The Young Martin

-

-

2nd African Baptist Church, Savannah, GA

-

-

Isaac McCaslin, General Rufus Saxton’s Speech at the Second African Baptist Church, charcoal on paper, 2015.

-

-

Classic Southern Church Signage

-

-

Front of 2nd African Baptist Church, 1926

-

-

2-Pac As 40 Acres & A Mule

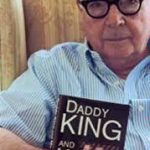

Through the years in Savannah, one of my favorite friendships belongs with notable writer and photographer, Murray Silver, Jr. His father, Murray Silver Sr, wrote the book, Daddy King & Me, about Martin’s father, or the other Martin, “Daddy King,” and the details of their long friendship. Murray Silver not only represented Martin Luther, Jr as an attorney, but he was also on the scene just minutes after Daddy King’s wife, Alberta was murdered in Atlanta in 1974 during the failed attempt on Coretta’s life. It’s odd, yet not surprising, that mainstream media “skips” mentioning this every year when they honor Dr. King. Or that Martin’s brother, Alfred, “A.D.” King drowned mysteriously after his brother Martin’s assassination. Clearly, someone wanted all of these beautiful people dead. To date, Murray Silver, Jr counts Coretta Scott-King offering him a role in helping to develop The King Center in Atlanta one of his life’s great honors. Both Silver men have countless stories and personal photos of the two families in casual gatherings and its that behind-the-scenes stuff of such people that is so priceless to other storytellers like myself.

-

-

Testament to a very special bond.

-

-

Murray Silver, Retired Judge & Storyteller

-

-

Daddy King said, “I can hate no man.”

-

-

Murray Silver, Jr & Coretta Scott King

-

-

Murray Silver, Jr, Author & Photographer

PART TWO COMING NEXT WEEK!